Case Study: How the EU ETS Has Encouraged Decarbonization

5 Min. Read Time

Does the EU ETS contribute to the decarbonization of Europe?

Emissions trading systems like the EU ETS exist to generate a price on carbon that encourages companies to invest in lower-carbon alternative processes and energy sources.

For many years Europe’s carbon price languished below €5/tonne, far below the level needed to make fossil fuel-powered processes relatively more expensive than their clean alternatives. But regulatory changes in 2017 to reduce the supply of carbon permits in the market triggered a surge in prices that earlier this year brought the price of EUAs to more than €100/tonne.

Has the EU ETS worked to cut emissions? The raw data suggests so, certainly when it comes to power generation.

In 2008, more than 11,000 installations covered by the market reported verified CO2 emissions of 2.1 billion tonnes. By 2014 this number had fallen to 1.8 billion tonnes, and in 2021, the latest year for which there is consolidated data, emissions had dropped to 1.3 billion tonnes.

To be sure, emissions reductions in the early part of the last decade – when the price of EU Allowances was less than €5/tonne, may not have been entirely due to the cost or carbon. Other regulations, such as the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED), also played a role. The IED, which entered into law in 2010, required that large combustion plants such as power stations should reduce emissions of various non-GHG pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulates. Plants had the option to invest in equipment to reduce these pollutants, or they could request a “limited lifetime derogation,” under which they would consent to operate the plant for a limited number of hours between 2016 and 2023.

This directive was a significant factor in a number of large coal-fired power plants being shut over the past few years, particularly in the UK, where at the present time, just two plants remain in operation. One of these will close permanently in September, while the last plant will shut in September 2024. In the wake of the IED, a number of countries also announced decisions to end coal use for power generation permanently.

According to research by the Beyond Fossil Fuels campaign group, 16 EU member states will be coal-free by 2030, while all but one of the remainder have pledged to leave coal by 2038 at the latest. Poland has set a 2049 end date.

To be sure, many of these declarations were made between 2016-2019. During that period, the EU was debating the first set of changes to the EU ETS for the period to 2030, which included a hike in the bloc’s emission reduction target from 21% by 2020 to 40% by 2030 (later updates took the 2030 target to 55%). The increase in EU-wide ambition mirrored national plans to wean their economies off coal.

The impact of these national policies can be seen in the decisions by power companies to shutter coal capacity. Germany, for example, the largest coal-fired economy in the region, has closed 34 units since 2012. These plants emitted 66 million tonnes of CO2 in 2006. Six of these plants were owned by RWE, making it the company with the largest number of units closed. The six accounted for emissions totaling 31 million tonnes in 2006, which had declined to 11 million tonnes by 2017, when the first of them was permanently closed.

Over the same period, the UK retired 16 coal-fired units, representing a massive 120 million tonnes of CO2 in 2006. As of 2020, just two plants were still operating, emitting a combined 1.6 million tonnes. UK plant operators were also subject to a surcharge on carbon emissions since 2010. The UK Carbon Price Support mechanism imposed an additional cost on generators after the government judged the EU ETS price to be insufficient, and emitters currently pay £18/tonne over and above the cost of UK (formerly EU) allowances.

To be clear, during this period, the price of EUAs was rising fast. At the start of 2018, the benchmark EUA price was €8.00. By the end of that year, it had jumped to €25.00 as the market absorbed the likely impact of the proposed market reforms, including the market stability reserve. By the end of 2021, EUAs had soared to €80.

Numerous stakeholders have pointed to the combination of the EU’s Industrial Plant Emissions directive, the rising price of EUAs (and later UKAs) as well as this carbon price support levy as hastening the end of coal in Great Britain.

But with coal plant emissions now falling as a result of rising carbon prices and other regulations, where does that leave the heavy industry?

Historically, the EU ETS has given generous grants of free EUAs to industrial sectors that it judges to be both energy intensive and exposed to international trade. Adding the cost of EUAs to any industry that struggles on thin profit margins in an internationally competitive market has been seen as counterproductive. This carve-out for the industry is set to end later this decade when the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is introduced.

CBAM will require imports of selected industrial materials – steel, cement, chemicals, for example – to pay a cost for the carbon emissions “embedded” in their manufacture. The EU will calculate the amount of carbon emissions represented in all imports and charge a levy comparable to the EU ETS price. But if, for example, steel is imported into the EU from a country where there is an “equivalent” price on carbon emissions, those imports will not need to pay the CBAM charge.

Europe’s CBAM proposal has triggered intense debate in countries with which it trades in these materials, with the UK, the US, and Canada all suggesting that they too will implement their own carbon levies.

The consequence of CBAM for European industry is that it will no longer need to be protected from the additional cost of carbon emissions. In conjunction with the CBAM legislation, EU lawmakers also passed updates to the EU ETS that will see the share of free EUAs handed out to industry begin to decline at a faster rate, eventually reaching zero after 2030.

This phase-out of free allowances will ramp up the cost pressures on the EU industry to invest in decarbonization at home rather than relying on trade protection from Brussels. The prospect of fully internalizing a carbon price that is already near €100 has already triggered innovation in new technologies such as green hydrogen and zero-carbon steel, and we will doubtless see more in the coming years. Moreover, the EU has pledged to support all measures to transition towards a low-carbon future through investments that are funded in part by the carbon market.

EUA auctions generated €38.5 billion in 2022, compared to €3.1 billion in 2014, the first year the daily sales were held. This money is shared among member states according to their share of the EUAs on offer, and they are required to use at least 50% of the revenue for “climate and energy-related purposes.”

The European Commission has reported that in 2021, 76% of the total auction revenues went on climate and energy measures. According to a Commission report, “most revenues were spent on renewable energy (30%) and transport (20%) projects. In addition, Member States funded energy efficiency, domestic and international projects, as well as research and development. Some 25% reported funding other emissions-reducing measures…[including] tax breaks and social support.”

Coal phase-out announcement timeline:

2015: UK

2016: France, Finland

2017: Sweden, Portugal, Denmark, Netherlands, Italy

2018: Ireland

2019: Hungary, Greece, Slovakia, Germany

2021: Spain, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Poland

2022: Czechia, Slovenia

Coal free: Belgium (2016), Austria (2020), Sweden (2020), Portugal (2021)

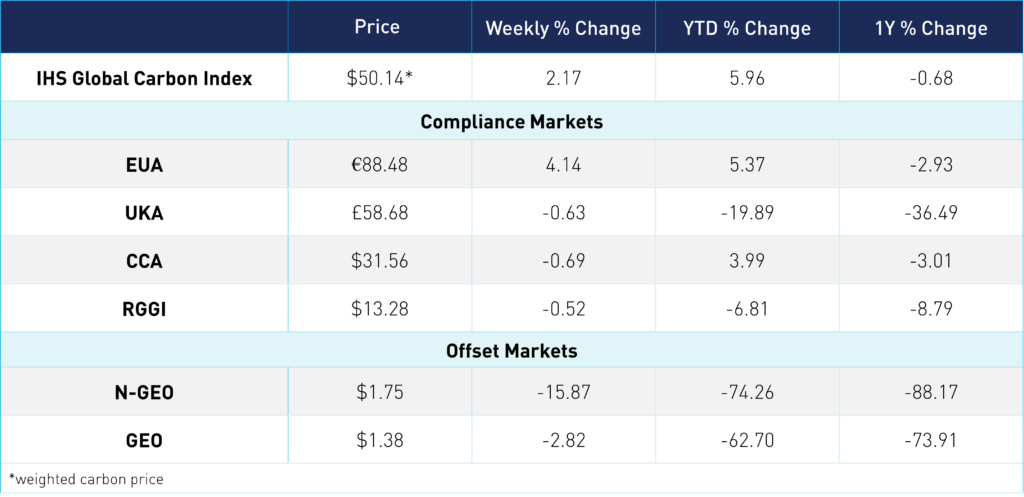

Carbon Market Roundup

The global price of carbon ended the week at $50.14. EUAs ended the week up 4.14%, at €88.48—the first weekly gain since early April. On Wednesday, EUA prices rallied 3% higher to close at €89.49 from what appeared to be some short covering. Prices continued to climb higher into Thursday, hitting a weekly high of €90.00. UKAs moved above £60 midweek but drifted lower to close the week at £58.68, down a slight 0.63%. Both US markets traded in a fairly tight range for the week, with CCAs at $31.56 and RGGI at $13.28. The offsets markets trended down for the week, with prices now both in the dollar range. N-GEOs are currently trading at $1.75 and GEOs at $1.38.

To learn more about our carbon credit ETFs, click here.