Carbon Markets are Nuanced: What the Guardian Article Missed

4 Min. Read Time

A recent article by the Guardian was critical of some carbon offset projects. It is important to note that, first, carbon allowances and the voluntary offsets the article referred to are two completely different markets. And second, there are nuances within the offsets market that investors should be aware of so they can better understand the arguments in the article.

There are key fundamental distinctions between the two forms of carbon markets, i.e., carbon allowances and voluntary carbon offsets. Carbon allowances operate through government-regulated cap-and-trade programs, where entities that emit over a certain threshold and fall under specified industries are required to participate in these markets (aka compliance markets). Many of these markets have been in operation for years and provide transparent pricing and emissions data. Voluntary carbon offsets, on the other hand, can be purchased by companies/entities looking to offset their emissions by investing in verified projects like reforestation or building renewable energy technology. The concept behind offsets is solid and presents a promising means of reducing and capturing emissions, though the offset market is less established than the allowance market. Greater scrutiny of offset projects is welcome as it should help better refine and guide the market to reduce any inefficiencies and problems with the credit offerings.

Carbon offsetting is one of the key mechanisms to achieving the ambitious climate targets under the Paris Agreement. It is a tool that allows nations, corporations, and even individuals to go beyond reducing their own carbon footprint or what they are expected to comply with under regulatory schemes (such as Emission Trading Schemes), to mitigate some or all of their unavoidable emissions. Carbon offsets are intended as supplements, rather than substitutes, to direct climate action. More critically, offsetting helps fund environmental projects that are unable to secure funds on their own. This is especially the case for nature-based offsets.

Nature-based carbon offsets, namely REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) projects, are some of the most popular in the market, and understandably so. REDD+ credits are cheap and can be easily attainable (i.e., by simply protecting existing forests from degradation). However, their integrity and role in climate action – a debate that, for decades, had been limited to the scientific literature – was brought to the public eye in recent weeks.

Behind the Guardian vs Verra Public Standoff

The Guardian started this controversy over offsets after making claims based largely on findings from one academic study by West et al. (2023), that over 90% of emission reductions created by Verra-certified REDD+ projects were actually ‘worthless’. The publication was followed by a number of opinion pieces by scientists and carbon market experts, including by Verra itself.

The debate is both good and bad news.

The good news is that carbon offsetting is now receiving the attention that has been long overdue, and the discussion around the quality of offsets is taking center stage in carbon markets. The offsets market is worth $2bn today and is expected to be worth $10-40bn by 2030. It is important to ensure that investment is being channeled into projects that have the highest impact.

The bad news is this kind of press is expected to create further uncertainty and lack of confidence in the offsets market, especially towards REDD+ projects. However, offsets are a critical means of making up for the shortcomings of current public policy and funding. Recent evidence from Brazil showed that avoiding deforestation cannot always be driven by governments or public policy alone but will also need to rely on private capital--the primary channel for funding the voluntary carbon market.

To understand the ensuing debate is to understand one of the key aspects of offsetting: how to set a ‘baseline’. A baseline scenario represents the counterfactual to the project in question or what would have happened had the project not taken place. Carbon offsets are created based on the difference between emissions that would have been generated in the baseline scenario (due to deforestation in this case) and those generated after project implementation (with each offset equaling 1 ton of CO2-equivalent avoided or reduced).

The Guardian’s article claims that baseline emissions in Verra’s projects have been overstated, i.e., they assume inflated deforestation rates in the baseline scenario.

Admittedly, setting a realistic baseline is a tricky task--merely as accurate as our ability to predict the future, which can be an approximation at best. As West et al.’s study and Verra use fundamentally different methodologies to assess REDD+ baselines, the divergence in their emissions reduction estimates is hardly shocking.

Specifically, REDD+ baselines compare the project area to another reference area where deforestation may occur. West et al. used a ‘synthetic’ approach to determine a ‘control’ or ‘proxy’ area that mirrors what would have happened in the project area in the project’s absence.

The problem is that this approach was far too simplistic.

West et al. chose a control area far from the project zone. Additionally, they assumed a generic set of physical variables that they deemed applicable to all projects, without regard for local deforestation factors characteristic of specific projects. The Guardian also fails to report a shortcoming that the authors of the underlying study themselves acknowledge: the margin of error is large, therefore the project area's rate of deforestation could vary widely (up to 256% between the three quoted studies). Moreover, the West et al.’s study remains a pre-print and has not yet been peer-reviewed by the scientific community.

Despite the flaws in the Guardian’s article, the debate has, without a doubt been an eye-opener.

There is still a long way to go towards optimizing methodologies for forest carbon projects, yet this should not come at the expense of funding REDD+ projects that would likely not be supported otherwise. For in the fight against one of humanity’s biggest threats, it is better to be vaguely right than precisely wrong.

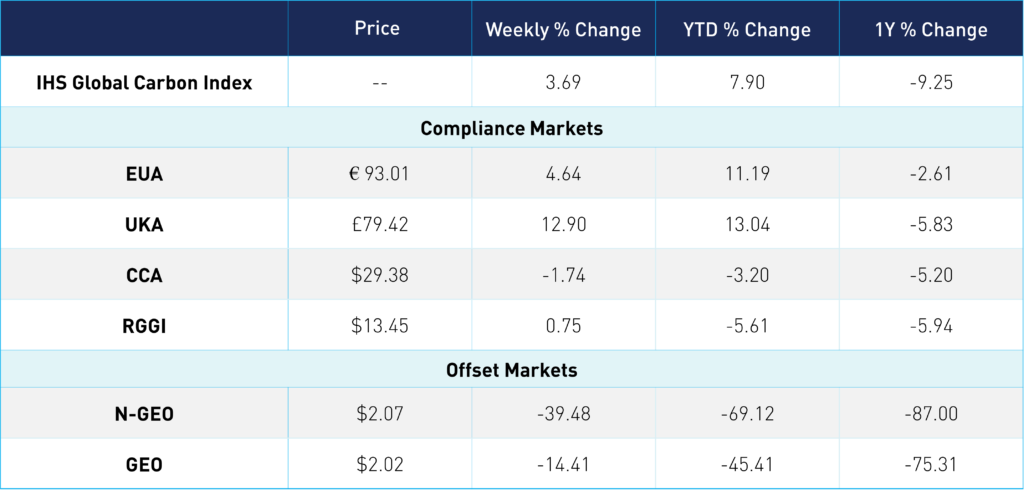

Carbon Market Roundup

EUAs had an impressive week, hitting a 5-month high on Wednesday at €95.45--just under the key €100 threshold. Prices have since revised down slightly, closing +4.64% for the week at €93.01. The recent rally appears to be largely driven by more positive economic sentiment and inflationary easing, as well as the drop in natural gas prices, which are currently less than a fifth of their peak last year. Revised forecasts for colder-than-normal temperatures, technical factors, and the confirmed April 30th allowance surrender deadline also contributed to EUA price action. UKAs also posted big gains, with prices jumping 12.90% over the week, closing at £79.42. Going into today, UKAs are pushing £82, which we haven't seen since early December. Both California and RGGI had a fairly quiet week, with prices remaining relatively flat, at $29 and $13, respectively. Voluntary offset futures have trended down for the week, with N-GEOs falling to the same $2 level as GEOs.