EU Law-Making: A Primer for the EU ETS Reforms

4 Min. Read Time

The European Parliament’s failure last week to adopt a position on the “Fit for 55” reform package for the EU Emissions Trading System has highlighted legislative procedure in the European institutions. In this article, we offer a brief guide to the process and relevant bodies that are involved in making EU law.

Overview

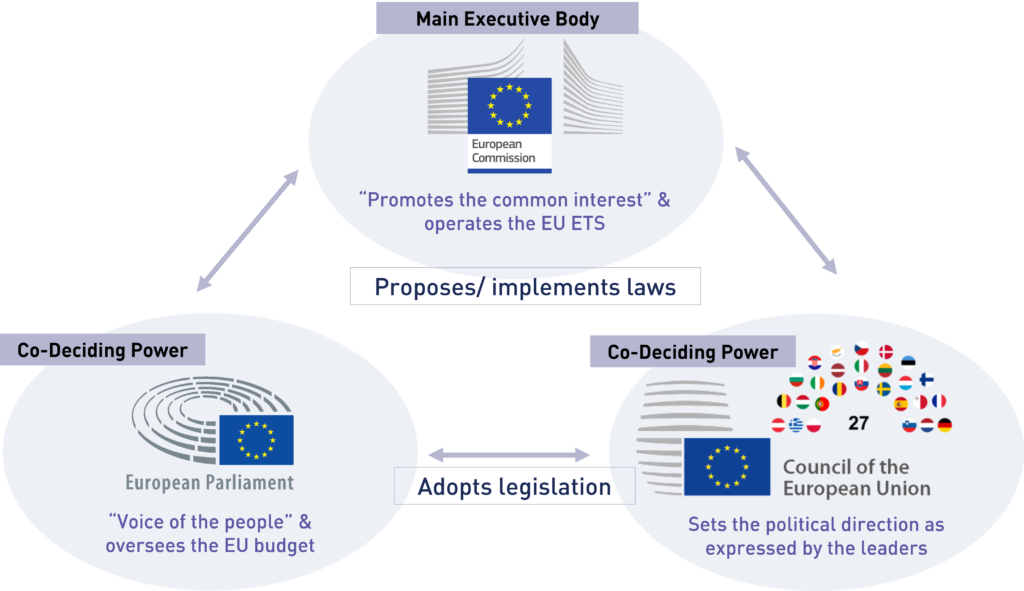

There are three main bodies involved in creating legislation: the European Commission, which is the only body that can propose legislation, and the European Parliament and European Council, which amend and pass laws.

The Commission is the EU’s executive – it is in charge of proposing and implementing laws and making regulations. The Commission operates the EU ETS and ensures that it is fit for purpose. Over the 17 years of the emissions market, the Commission has made rapid adjustments to the regulations – such as beefing up the security measures to prevent fraud – and proposed more long-term legislative changes, such as the current reform package, which is designed to take the market through to 2030.

The Parliament acts as the bloc’s legislature. It examines and amends proposed legislation on behalf of Europe’s citizens and oversees the EU budget. The assembly is divided into seven main groups, each representing political affiliation instead of nationality: European People’s Party (EPP, centre-right), Socialist & Democrats (S&D), Renew Europe (centre left), Greens, Identity & Democracy (I&D, right), European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR, right), and the Left group.

As of the 2019 Parliamentary elections, the largest party was the EPP with 187 members of the parliament (MEPs), followed by S&D with 147, Renew with 98, I&D with 76, Greens with 67, ECR with 61, and the Left with 39.

An experienced member of Parliament is charged with supervising the passage of each piece of legislation through the house. The role of the “rapporteur” is key to the success of the legislative process, since he or she must engage with fellow MEPs to ensure a majority in favor of the bill in both committees and in the plenary.

The European Council is made up of the leaders of the 27 member states, but at times can be made up of relevant national ministers when it is dealing with specific issues. The Council sets the political direction of the EU as expressed by the leaders.

What happened with the Fit for 55 package?

The current “Fit for 55” package was first proposed by the European Commission in July 2021. It seeks to raise the ambition of the EU’s climate policies to help achieve an economy-wide cut in emissions of 55% from 1990 levels by 2030.

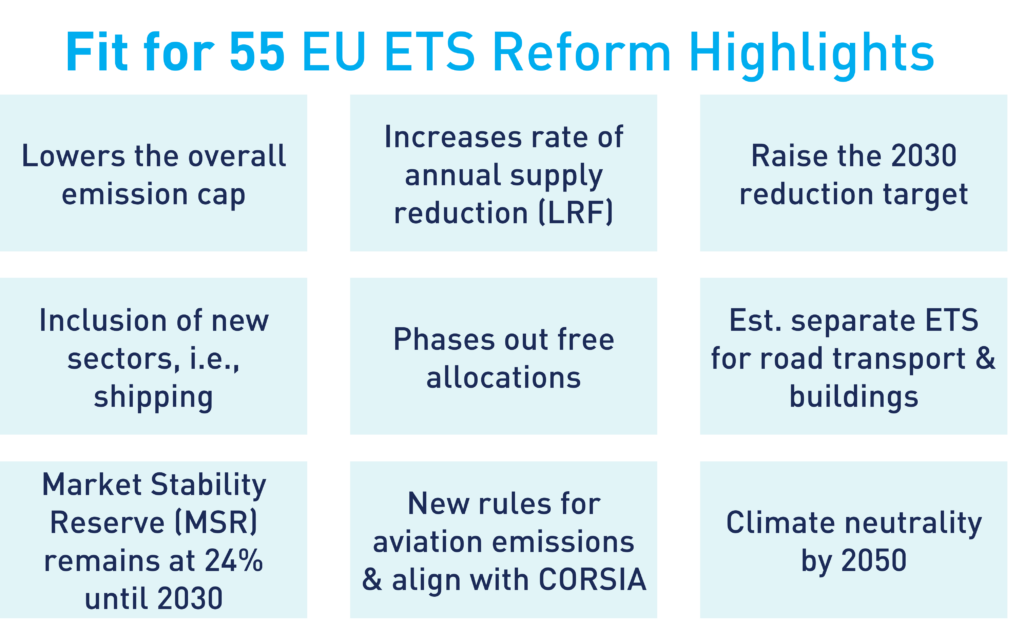

To achieve this, the Commission proposed that the EU ETS set a reduction target of 61% for 2030, compared with the existing 43% goal. This would require a reduction of the overall cap on emissions under the carbon market, achieved through a larger annual reduction as well as a one-off “rebasing” of the cap.

The “Fit for 55” file was passed to the European Parliament, which delegated to its environment Committee (known as ENVI) to study the proposals and make relevant amendments. This process has taken the last few months and culminated in ENVI formally adopting its “report” on the file with a long list of proposed amendments in mid-May.

The report was presented to a plenary sitting of the Parliament last week, though not before a long list of additional amendments had been tabled for MEPs to consider.

Parliamentarians from both the left and right of the assembly opposed many of the changes that had been made by ENVI, while voting to adopt amendments of their own. The confusion in the chamber led the rapporteur, Peter Liese of the European People’s Party, to ask his party group to vote against the adoption of the report. In this, he was supported by the socialists and democrats group. The assembly further voted to refer the report back to the committee, and ENVI will begin the work of revamping its proposal this week in June 13.

What is to come?

Leaders of the party groups in Parliament have scheduled a second plenary hearing for the file on June 22, when they hope to formally adopt the legislation and move on to the next stage.

Once the file has been passed out of Parliament, the European Council meets to take note of the amendments made by the Parliament, and to establish its own position on the legislation.

The penultimate stage of legislation is known as “trilogue”, and is essentially similar to the reconciliation process in the US Congress. The Council, Parliament and Commission meet to develop compromises on any sticking points and to develop a single text that is acceptable to all three institutions.

The file is presented to Parliament for final approval, and to Council for its adoption. Legislation becomes law once it has been published in the Official Journal of the EU, and the Commission then takes up the work of implementing the legislation.

The EU ETS reforms may be adopted by the full Parliament by the end of June, which observers say would still give time for the Council to adopt its position on the file by July.

This would then allow trilogue discussions to begin after the summer break, and for the law to be adopted around the end of the year.

What is the “Fit for 55” package?

In the wake of the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the European Commission proposed an ambitious package of measures to kick-start the region’s economic recovery and to speed up the transition to a fully green economy.

The “Green New Deal” covers the entirety of the EU economy, from energy and materials through to services, recycling and consumption.

As part of the Deal, the Commission proposed a revamp of the EU ETS, called “Fit for 55” after the agreed goal of cutting emissions by 55% from 1990 levels by 2030.

The program will see adjustments to the market’s overall cap on emissions to bring the trajectory in line with the new target, steeper annual cuts in the cap, the inclusion of maritime emissions in the market and continued assistance for countries to transition away from fossil fuels.

“Fit for 55” also envisions a separate and new cap-and-trade system covering emissions from households and transportation, a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism to encourage industrial emissions cuts and prevent carbon leakage, and a Social Carbon Fund to dampen the impacts of higher costs on the most vulnerable citizens.